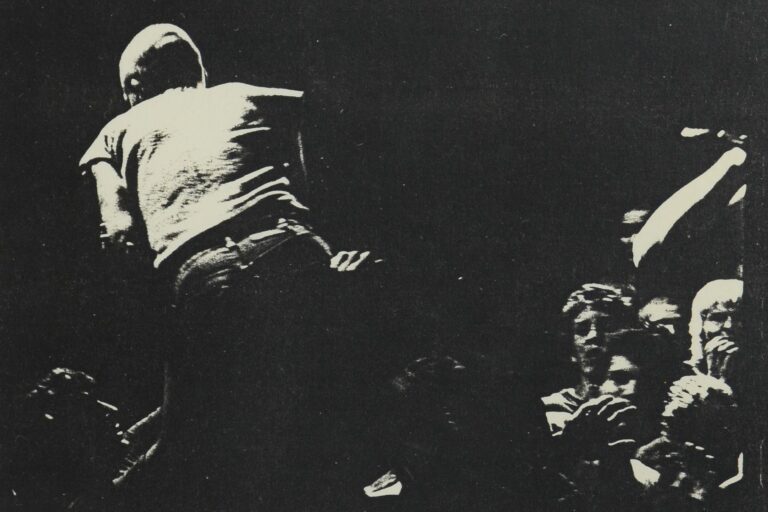

Images from the D.C. punk archive.

Washington, D.C. native musician Ian MacKaye, vocalist of bands like Teen Idles, Minor Threat and Fugazi, is most likely the reason you have black marker on the backs of your hands the day after a concert.

MacKaye, now 62, was a teenager when the punk and hardcore, sometimes spelled harDCore, scenes in D.C. were becoming something, yet because he was below the legal drinking age, he was often not allowed into venues.

“When I first started going to punk shows I was underage. It was really upsetting to be blocked from getting into seeing the bands, that you can’t believe that you waited your whole life to see or they’re a band that you love, and they come to play your town and you can’t get in because you’re a certain age.”

Nine o’clock, no stamp on your hand

It’s hard to rock when you can’t see the band

Minor disturbance, stopped at the door

You missed another show because of your age

“Too Young to Rock” by Teen Idles

The practice of marking underage kids’ hands with X’s was popularized in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The original 9:30 Club, a venue crucial to the punk scene in the city, opened in May of 1980, the same year MacKaye and the Teen Idles took a Greyhound bus from D.C. to California with two guitars, two drumsticks and two roadies for a summer tour.

They played Mabuhay Gardens in San Francisco, where “they did card, but they let everybody in. And we were like, ‘How’d that work?’ And [they] just put an X on these kids’ hands because then you see [if they’re] holding a beer. And we’re like, ‘oh! that’s a really good idea. That’s a really brilliant idea.’”

Leave it to kids in the punk community to dissect local liquor laws for their love of live music. Coming back from tour, the Teen Idles brought what they saw at Mabuhay Gardens to the 9:30’s owner and manager at the time, Dody DiSanto (formerly Bowers). The club was still 18+, mostly because the drinking age in D.C. was 18 until 1986. MacKaye explained they found a law, nicknamed the “Popcorn Law,” that says that a percentage of sales at a place that sells alcohol must come from food, which then technically makes the venue a restaurant, and you can’t prevent people from coming into a restaurant. “We knew [it] was within their ability to let kids in.” He and his band convinced DiSanto they would police minors to make sure they weren’t drinking and she let them play the show.

“We went to her and we said ‘listen, let the kids in.’ Because the kids, that’s the future, that’s the scene, and the scene is huge, but we’re mostly under 18. I said, ‘put X’s on their hands.’ We don’t want anything to threaten access to seeing music.”

In the middle of a thought about how it’s “a crime” that venues dictate who can see shows based on whether they are potential customers for the bar, MacKaye asked me how old I am, to which I replied 21. “Did you like music last year?” he said. Very, very much, I said. I’ve gone to over 75 shows, and that didn’t all happen since my last birthday. All-ages venues are as important, if not more, to the concert-goer as they are to the band trying to sell out a room.

Opening the 9:30 Club to all ages helped the live music scene, especially the punk and harDCore scenes, explode. DiSanto is hailed as being instrumental in building that music community in D.C. She opened the club doors to these kids, creating a sort of unspoken agreement between the 9:30 and the punks.

“I don’t think [Mahubay Gardens] were thinking ‘this is being revolutionary.’ I just thought, okay, this kid can’t drink. We’ll let him in but he can’t drink. That’s all. We made it more political because we saw the absurdity of the laws here,” MacKaye said.

Went to the Bayou, they said, “No”

You’re not eighteen, you can’t see the show

“Teen Idles” by Teen Idles

“I can remember going to The Bayou on K St. and The Damned were playing with the Bad Brains. I was 17 and I was absolutely desperate to get in. And so I paid a friend of mine who was a Naval Sea Cadet and he stole some blank photo ID cards off his commander desk and sold me one for 10 bucks.”

The ID was of someone who was about a year older than him and with blue eyes like MacKaye’s, but the Bayou, a now-closed 500-capacity Georgetown venue, was especially tough on fakes. MacKaye bought a laminating kit and stuck a polaroid of himself to the military ID. The bouncer was about to turn him away, when someone hit him with an ‘oh sorry, you don’t accept a U.S. military ID?’” MacKaye saw The Damned with the Bad Brains that night.

MacKaye is adamant about increasing access to music. It’s palpable how much it meant to him to see all these live shows when he was young. He told me he’s never knowingly agreed to playing a show that wasn’t all ages. “Having all these younger kids who are part of our crew and knowing that they couldn’t get in, that just drove me nuts.” His brother was one of those kids, younger by three years, who would often just sit by the backdoor of the venue and listen to the show from outside.

MacKaye would often opt for the X by handing bouncers a Roy Rogers (yes, the fast-food chain) Buckaroo Club Member card, to which he’d added his name, Ian MacKaye, and ‘I am not over 18,’ both written in Crayon. It was another way to humor and underscore the “absurd practice” of 18+ venues.

Drawing X’s on one’s hands only later became associated with the straight edge movement, which MacKaye is credited for popularizing, where participants sport the X’s to proudly show they don’t drink or use drugs.

“Part of being a punk in my mind was seceding from the mainstream. Not being a part of how things work. Subverting the practices that we thought were biased or repression or whatever. I think that this was a way of joining the minority which was younger aged kids.”

—

Me: Do you think the X’s catalyzed the live music and punk scenes here in D.C.?

Ian: “You’ve been here four years, have you seen any bands?”

Too many to count.

“So wouldn’t you say there’s been a bit of a revolution? Where are you from?”

I grew up in Brazil and then I lived in Pennsylvania for a little bit, Pittsburgh… All the concerts I went to in high school when I was there, like I was what, 16, 17, they let me in with the big X’s on my hands, but they let me in.

“You answered your own question.”

—

Just last month I went to see Snail Mail, a band I’ve loved for years at DC9. The second opener was a local three-piece, Birthday Girl DC, whose bassist is also Mackeye’s niece. Their lead vocalist, daughter of Brendan Canty of Fugazi, recently turned 16 and the X’s on her hands, albeit small and thin, were clearly visible from the stage. A large portion of the audience also sported X’s, a symbol of the next generation of music starting young and being fed by those in the crowd with black marker on their hands.

“It’s always got to be for all people. Music is for all people,” MacKaye adds.

Wow, reading about Ian MacKaye and the history of the punk scene in D.C. really takes me back. As someone who grew up in the city, his music and influence were impossible to escape. I remember going to shows and having that black marker X on the back of my hand, proudly showing that I was part of the scene. It’s amazing to think that such a simple idea, born out of frustration with being too young to enter venues, has become a tradition that still lives on today. Thank you for sharing this piece of history and shedding light on the genius behind it. Keep rocking!